The Guess Worker

The concept

Overview:

- A concept is a linkage between two sets of information.

- More sets of information have to be linked together "two by two".

- Without symbols the number of layers of concepts that can be built up is small.

- Humans have an exceptional ability to link concepts together using symbols.

- This ability allows us to form concepts of great complexity.

The word concept means different things to different people. In everyday speech it has a similar meaning to the word idea. However, beyond knowing that we have concepts and that they happen inside our heads, it's difficult to put a finger on what exactly they are.

I like to define the word concept as the linkage between any two sets of information. This definition gives the word a simpler and broader meaning than in its usual sense. It means that a concept can be conscious or unconscious. And it can be anything from the linkage of "the sound of a bell" and "food", to the linkage of "E" and "MC2".

But, of course, this still leaves a lot of questions unanswered. What are the linkages made of? How does the mind get the information it needs from them? How is information stored in them? How do the linkages form in the first place?

Repeat simultaneously

Let's think about the last question. How did Pavlov's dogs form the concept "the sound of the bell means food". First, the bell ringing and the food were repeated frequently. So, we can say that repetition of stimuli is needed to form and strengthen a new concept.

Second, we know that the two stimuli were presented to the dogs simultaneously – or nearly so.*1 Another conclusion, then, is that concepts are more likely to be formed if the stimuli occur close to each other in time.

These two conclusions make sense. Our world is causal and so animal brains have evolved to establish the connections between causes and effects. If two events occur one after the other in the same location, then it could be that the first event has caused the second. If the second event always occurs shortly after the first, then there is very likely to be a causal link between the two events. Animal brains, then, have been evolved to make a linkage between two such events and to make that linkage stronger the more often the two events occur together.

Can three sets of information be linked in a concept?

Of course causality is frequently not as simple as one event causing another. Two or more causes may result in one effect and one cause may result in two or more effects. Perhaps, then, animal brains are capable of associating three or more stimuli? Let's say dogs are exposed to three stimuli: flashing light, the sound of a bell and food, but food is not given if one of the first two stimuli is missing. Can the dogs associate all three stimuli simultaneously?

It is impossible to answer this question without knowing what is happening inside the dogs' brains. The reason is that from outside we can't tell if all three sets of information are really connected only at one linkage point. It is possible instead that the dogs associate two sets of information at one linkage point and the third set is only associated later.

This means that the dogs may first associate the flashing light with the sound of the bell to make one concept, then associated this concept with food to make a further concept.

Humans, of course, have no problem associating multiple sets of information. Here's an example: Red sky at night, shepherds' delight. Even though this sentence contains many concepts, the important association is between three ideas which are causally linked in the following way:

Event A + Event B = Event C

Which in this case is:

1) Red sky + 2) Night = 3) Good weather.

Can humans make a single concept by associating three such sets of information at one linkage point? Maybe, but, just as with the example of the dogs, they also could associate two of the sets of information to form a concept and then, by associating this concept with the third set of information, form a second concept. The difference between this example and that of the dogs is that here humans use symbols to make associations. With symbols there really is never any need to associate any more than two sets of information to form a concept. By associating concepts with symbols and then associating symbol-concepts with symbol-concepts, concepts can be built up upon each other almost without limit and always by linking two sets of information at a time. (Here, the concept of night has become linked to the word „night“ and the resulting symbol-concept is linked to the symbol-concept „at“ to give us a new symbol-concept „at night“. The symbol-concept „red sky“ is then linked to give us the symbol-concept „red sky at night“...and so on.)

Humans, then, have an exceptional ability: using symbols they are able to develop highly complex concepts. Because of this ability they have even less need than other animals to associate more than two sets of information at one linkage point. Even the most complex concept can be built up by associating symbol-concepts in stages, two-by-two.

It could be, though, that it is impossible to associate more than two sets of information at any linkage point. This may be why other animals aren't able to develop their concepts in the way that humans can. Humans get around the „two-sets“ limitation by layering concepts upon each other - and they do this by using symbols.

From concept to symbol-concept

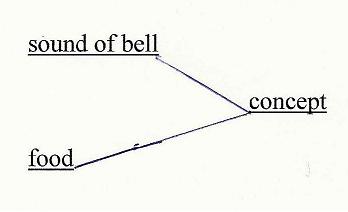

Very probably, then, a concept - in all animals including humans - must always be a linkage between just two sets of information. This linkage can be represented in the following way for the Pavlov dogs' concept:

"

"

Or generally, for any concept:

"

"

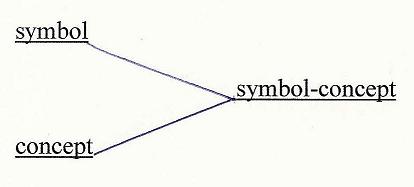

The linkage of a concept to a symbol could then be represented in a similar way:

"

"

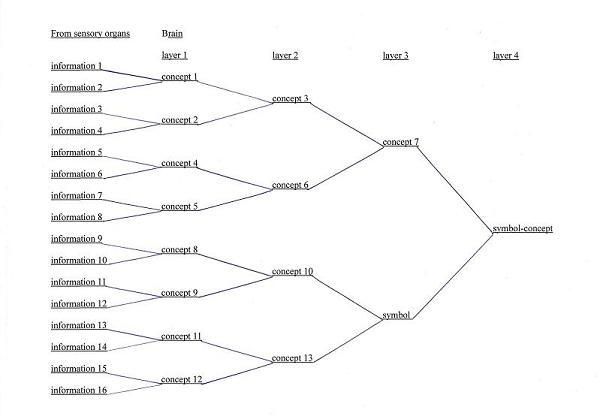

The resulting "symbol-concept" (a concept in itself) can then be linked either to further concepts or or to other symbol-concepts. Here is a diagram to illustrate how such linkages are built up, layer upon layer:

"

"

Do the linkages in our brains connect up in neat layers as in the above diagram? Very probably not. I would guess that the network in our brains probably looks more like one of Tony Buzan's mind maps (see www.thinkbuzan.com/gallery) with linkages branching out in all directions. These mind maps exclude concepts considered to be obvious. To draw a realistic representation, we would need to include all concepts including those which aren't linked to any symbol, and therefore can't be expressed in words.

How many layers of these "asymbolic" concepts are needed before we can form a simple symbol-concept such as the word "cat"? It's hard to know - not only because the layers contain concepts which can't easily be expressed with symbols, but also because the smallest unit of information needed to form a concept is not known.

Despite these unknowns I'm going to attempt to draw a relatively realistic representation of what the network of concepts in the brain might look like. To do this, I'm going to impose on myself three rules:

1) I can link any concept to an unlimited number of other concepts in the same layer.

2) If concepts aren't linked to symbols, I can build up only to a maximum of four layers of concepts.*2

3) If concepts are linked to symbols, I can build up an unlimited number of layers of concepts.

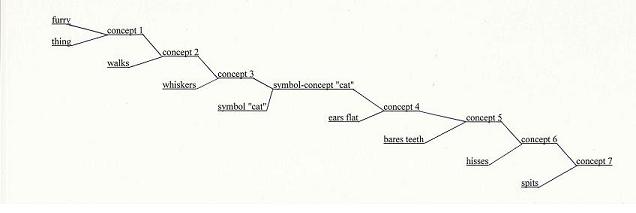

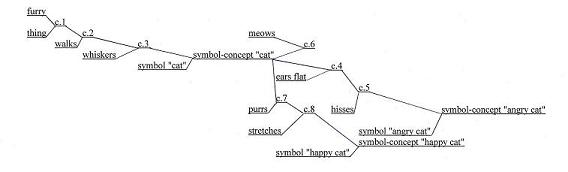

So, what would the network of concepts look like if these rules are applied? In the following diagram I'm going to consider how a child might learn the word "cat". In it I'm assuming that to learn what a cat is, a child must first know that it is a furry thing which has whiskers and walks. I'm also assuming, for simplicity, that the concepts "furry", "thing","whiskers" and "walks" are first layer concepts. (In reality they almost certainly aren't.) All the levels need to learn the symbol "cat" are also omitted. I use the word "concept" to represent concepts which can't be expressed simply in words. Here is what I came up with:

"

"

So, in the diagram above, the first three layers of concepts are asymbolic, but the fourth must be a symbol-concept - the word "cat" linked to the previous three layers. The asymbolic concept "hisses" can only be linked after the symbol-concept cat, because if it were linked before there would be more than four asymbolic layers - which is not allowed. The asymbolic concepts "ears flat","bares teeth","hisses", and "spits" could all conceivably be linked in layers - but again four layers is the maximum before another symbol-concept (such as "angry cat") would be needed.

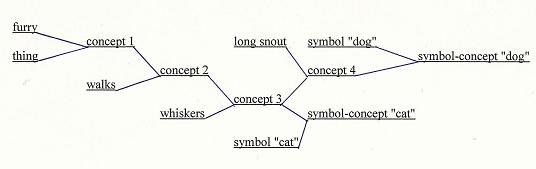

Is this last diagram realistic? Probably not much. What is missing from the diagram is the multiple connections that each concept can make in the same layer. I can't include them all, because that would make the diagram impossibly complex. So I'll include only some of them in the diagram below.

"

"

(c.= concept)

As you can see the result is already beginning to look like a mind map.

How can two concepts be distinguished?

But how does such a network allow two concepts to be distinguished from each other? How, let's say, could a child learn that a cat is different from a dog? In the following, I'm going to assume that a child can distinguish between a cat and a dog without using symbols. Let's also say that the child uses the concept of "long snout" to form the concept of a dog:

"

"

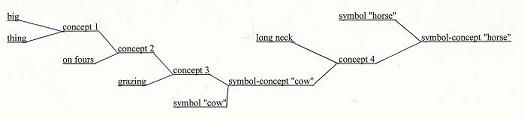

The concepts of a dog and a cat are not that complex and do not need many layers - and could possibly still be distinguished asymbolically. But once concepts get more complex, symbols are needed to make distinctions. For example, symbols are probably needed to differentiate between a horse and a cow:

"

"

In other words, because the concepts for "cow" and "horse" are complex, needing four layers before the symbol-concept is formed, cows and horses cannot be distinguished from each other asymbolically. The concept of a horse must therefore be learnt through the symbol-concept "cow".

Symbols, then, are needed to build up complex concepts and complex concepts can't be distinguished from each other without the use of symbols.

Many animals use symbols – the wagging tail of a dog, for example, can symbolise "I am pleased to see you". Humans, though, seem to have an exceptional ability to build up concepts using symbols alone. Symbol-concepts can be layered upon symbol-concepts to an almost unlimited complexity. It may be that this ability is the only significant difference between us and our closest primate relatives. It is a difference, though, which is responsible for the vast gulf in mental capacity between us and the rest of the animal kingdom.

Why all the rules?

It's all very well to hypothesise that concepts are built up in the way I have described, but my arguments are less than satisfying without a great deal of extra explanation. Why, for instance, did I impose three rules on myself in drawing the networks above? Is there any reason to believe that these rules have something to do with what is happening in the brain?

And what is so special about symbols? What is about them that allows concepts to be built up above a limited number of layers?

Why, too, don't we think about cows whenever we think about horses? If we learn what a horse is through the concept of a cow, then why don't both concepts come to mind when we think of either one of them?

I believe the answer to these questions has to do with the way consciousness works. So far in this post I haven't mentioned consciousness. But when it comes to concepts, consciousness can't be avoided forever. Consciousness must play an important role in both how we use and how we make concepts. What that role is, is something I want to investigate in a future post.

*1. Increasing the time intervals between the two stimuli affect the ability of the dogs to make the association. If the bell was rung in the morning but the food wasn't given until the afternoon, it's unlikely that the dogs would make an association between the stimuli.

*2. I have chosen a small number (ie. 4) to make the diagram more manageable. In reality the number is probably much larger

Comments powered by CComment